INTERVIEW

In Conversation: Sofia Pashaei & Morteza Khakshoor on Narrative and the Politics of Representation

For their joint exhibition at EDJI Gallery, contemporary artists Sofia Pashaei and Morteza Khakshoor bring together two distinct yet resonant practices that explore personal and collective memory through figurative painting. Both artists are known for creating emotionally charged images that feel like stills from a larger story. These quiet moments hold tension, intimacy and open-ended questions. In this conversation, they reflect on the narrative forces behind their recent works, the relationship between perspective and perception, and how gender, identity and diasporic experience inform their visual language.

THERE IS A NARRATIVE AND QUITE CINEMATIC QUALITY TO BOTH OF YOUR INDIVIDUAL PRACTICES. IN LINE WITH THIS, WHO OR WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER THE NARRATOR OR NARRATIVE FORCE IN YOUR WORKS FOR THIS SHOW?

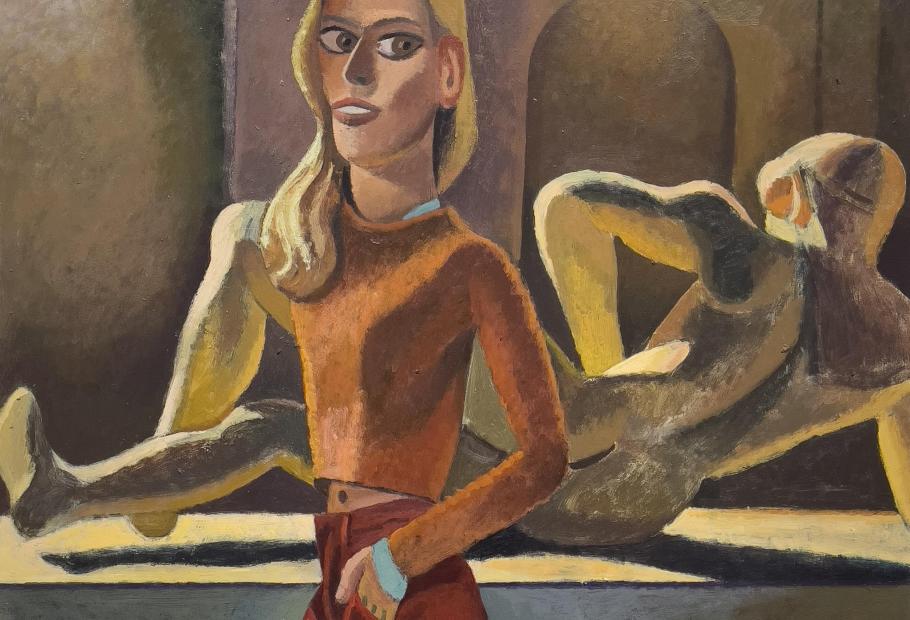

Morteza Khakshoor: Whether there are cinematic or theatrical qualities in my pictures or not, I am certainly fascinated with both media. The storyline, dialogue, characters, sound, and music are usually secondary for me. A great film or play works best when it constructs impactful singular frames that can be looked at, explored, and—more importantly—experienced independently of those elements.

In other words, if I am not struck by the visual qualities within individual shots, there’s not much to engage me. I am fascinated by fleeting moments when the arrangement of visual motifs tells me something about the characters or the scene. This, to me, is far more profound than simply following a storyline over 90 minutes. The plot of most films can be summarized in a few sentences. But a great movie—take any of Antonioni’s trilogy, for example—can communicate everything through each frame rather than just showing the actions and reactions of its characters. This is perhaps where my practice aligns most with cinema or performance-based media. I should also mention that photography, particularly fashion photography and photojournalism, plays an equally influential role in my work.

I think the narrative force in my work, especially for this exhibition, is the psychological and emotional state of the protagonists I allow to lead each image. The figures, regardless of what they appear to be doing or their relation to their surroundings, are captured in moments that prompt questions: Who are they? Where did they come from? What just happened—and what’s next?

Until recently, male characters and their behaviors were the sole subjects of my figurative paintings. I think that will continue to be a key theme, as masculinity, manhood, and their layered implications—especially their entanglement with power, identity, sexuality, and vulnerability—are enduring fascinations for me. It’s not admiration or critique of manhood per se, but rather its full complexity that captivates me.

That said, a new shift has occurred in this body of work with the appearance of several female figures and their visual competition with the men to dominate the picture plane. This is unprecedented in my practice. It feels as though—metaphorically—I’ve introduced a new set of colors to my palette, expanding the possibilities for different narratives. The change in perspective and point of view from one work to another has been especially interesting in light of this development.

THERE IS A NARRATIVE AND QUITE CINEMATIC QUALITY TO BOTH OF YOUR INDIVIDUAL PRACTICES. IN LINE WITH THIS, WHO OR WHAT DO YOU CONSIDER THE NARRATOR OR NARRATIVE FORCE IN YOUR WORKS FOR THIS SHOW?

Sofia Pashaei: Having started as an animator, I often return to the way painting holds space for contemplation in a way animation rarely does. I find myself constantly comparing the two—how they shape time, how they guide the viewer, and how they tell stories. A painting invites lingering; its meaning shifts depending on when you look at it, how you feel, or what you bring to it. It exists in a state of quiet permanence, where every detail, shadow, and gesture stays in conversation with the viewer for as long as they allow.

Animation, by contrast, sets its own pace. It pulls the viewer along a rhythm, frame by frame, where each moment builds on the last and quickly gives way to the next. There’s less room to pause, to wander, to return. And yet, I’m still drawn to how the two forms overlap. Both rely on composition, rhythm, and a sense of movement—even in stillness. A good painting feels alive not because it moves, but because it carries the suggestion of a before and after.

Recently, a close friend—someone not from the art world—asked me what excites me most in a piece of art. For me, it's always the narrative within it. Whether it’s found in a quiet gesture or a densely layered image, it needs to move me, make me feel something, invite empathy. At the core, it’s always about storytelling. What stays with me is when I sense the artist fully owning their narrative—making deliberate choices and opening up a space for connection through their work.

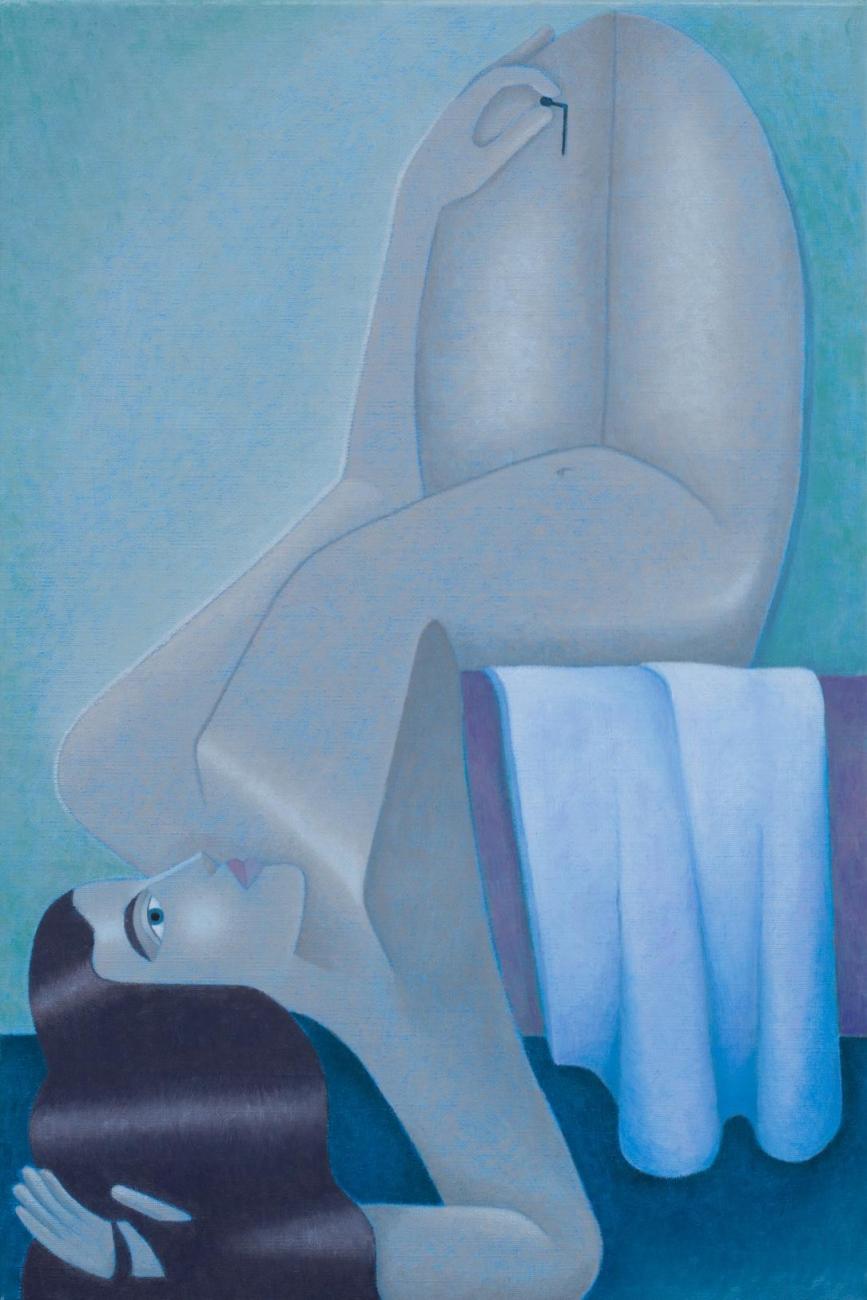

This series in particular is quite personal. It turns inward to explore my relationship with my sister. Growing up, we had what we called the “pink sistership”—a closeness that felt larger than just being siblings. At times, she took on the role of a mother, not because our own mother wasn’t present, but because cultural and language gaps sometimes made it difficult for her to reach us in the ways we needed. Now, watching my sister become a mother herself, I feel our bond shifting—growing fuller, more complex, and tender in ways I hadn’t expected. I began working on these paintings while she was giving birth to her second daughter. It felt incredibly moving, like I was not only reflecting on who we were but also witnessing the beginning of a new pink sistership forming.

Reflecting on how nurturing female relationships are has pushed my work to dig closer and zoom in—both emotionally and visually. In the most vulnerable moments, the gestures of the figures are blown out, closely tied, and intimate. In other moments, the canvases become smaller, the figures more simplified—a quiet homage to the simplicity that childhood and adolescence evoke when we look back.

HOW DOES YOUR WORK AND THESE NARRATIVE ELEMENTS RELATE TO PERSPECTIVE VS. PERCEPTION? HOW DO YOU THINK ABOUT (OR MAYBE EVEN TRY TO MANIPULATE—OR NOT) THE VIEWER'S PERCEPTION VERSUS THE PERSPECTIVE YOU'RE CHANNELING THROUGH YOUR WORK?

MK: I assume this debate around the artist’s intentions versus the viewer’s perception has been ongoing forever. I can’t say I’ve ever given it much thought—nor does it concern me as an artist. As far as I know, I make the things I make for me, and only me.

That said, I don’t completely rule out the possibility of unconscious desires or motivations around how my work might be received. I can’t speak for those subconscious impulses. For me, making images is not a tool to communicate clear messages. If I wanted to communicate something explicitly, I would have chosen writing. Painting is how I explore and make sense of what stirs my curiosity and perception. This includes both formal and conceptual concerns, which are equally important to me.

I don’t think about how viewers will interpret the work. Nor do I believe it’s my role to do so—even if it were possible. When a painting leaves my studio, my part is done. The work becomes a record of an internal conversation that’s now over. From that point on, it’s between the viewer and the painting. Whatever dialogue may or may not happen is not mine to shape. I truly believe this. That doesn’t mean I’m not interested in what others see or feel—it’s often amusing and meaningful to hear. The wilder and more unexpected the response, the better.

SP: In my practice, I think of perspective as being rooted in lived experience—relationships, memory, and the emotional textures that define them. Perception, meanwhile, belongs to the viewer, and the space between these two is where the most interesting tension lives.

I actually believe most people today are highly skilled at reading images, especially in a visual-first world. That opens up space to explore how perception can be stretched—through gesture, scale, and composition. Together, these form the visual language I use in my figurative painting.

This world often sits somewhere between flatness and depth—graphical yet dimensional. That in-betweenness isn’t just aesthetic; it mirrors the diasporic experience of existing in translation, navigating between cultures, and performing belonging in spaces where you never fully fit. There’s something artificial in that—but also poetic, and deeply human.

So, while I don’t try to control how someone interprets a piece, I do think carefully about how to create just enough friction or softness in a composition to make someone stay. That lingering is key—it’s what allows perception to shift and settle in unexpected ways. It mirrors how I revisit my own memories: sometimes sharp and vivid, other times soft and elusive.

Color plays a quiet but vital role in shaping the emotional rhythm of the work. Every canvas begins with a blue underpaint—specifically a tone inspired by Persian blue. It simmers just beneath the surface, like how Persian culture quietly grounds my experience. This blue becomes an emotional undercurrent, adding depth and continuity across the series.

In this new series, I’ve moved away from recurring motifs that once served as visual cues. Instead, I’ve stripped the compositions down—letting the scale of the figures and the intimacy of gesture carry the narrative weight.

The series feels especially personal because it touches something more universal than the diasporic condition—it speaks to the emotional architecture of sisterhood and the broader female experience. At its heart, these paintings are about women being a home for one another. Sisters who shelter each other. Care that is both immense and quiet. The gestures are tender—sometimes protective, sometimes so intertwined they become a single form. I want the viewer to feel that closeness—not just witness it. Whether through nurturing postures, compressed space, or the balance of softness and strength, the aim is to create a sense of emotional recognition. A visual empathy. This is about women holding space for one another—across time, generations, and cultural dissonance.

IN/BETWEEN

Discover Mortza Khakshoor & Sofia Pashaei's duo exhibition at EDJI Gallery.